By all accounts, I should love the Nathan’s Famous hot dog eating contest. It’s a spectacle of bad ideas, a carnival of culinary excess. It’s got bright colors and loud noises and men named “Joey Chestnut.”1 And I find it all completely depressing.

Have you ever watched a man unmake a hot dog with such joyless efficiency? He’s dipping his bun into a paper cup of water! He’s squeezing it into a bolus with his fist! He’s working his hardest to experience nothing—the most nothing!—and to experience it faster than anyone else.

When people bang on about “empty calories,” they’re almost always talking about processed convenience food—soda, candy, chips. But there are so many ways to be empty, so many ways to feel full.

Food for me has always been about pleasure and curiosity—let’s just say “experience” and cap it there. Don’t misunderstand me: I, too, wish to eat 40 hot dogs. But I'd prefer to take mine leisurely, over the course of an afternoon. More importantly, I'd prefer to take mine with toppings. I have long fantasized about sampling every hot dog configuration in this famous infographic in one sitting, comparing them against one another and taking notes. (Never mind that I have lived in Kansas City for more than a decade and never once seen the purported "Kansas City" dog.)

The primary obstacle to that fantasy—aside from the obvious health and environmental concerns—is cargo room. I don’t have Joey Chestnut’s stamina.

The solution was obvious: What I needed was a small-time sausage, a miniature meat stick, a diminuitive dog. I needed a slider, a smokie—li’l.

A brief history of abbreviated dogs

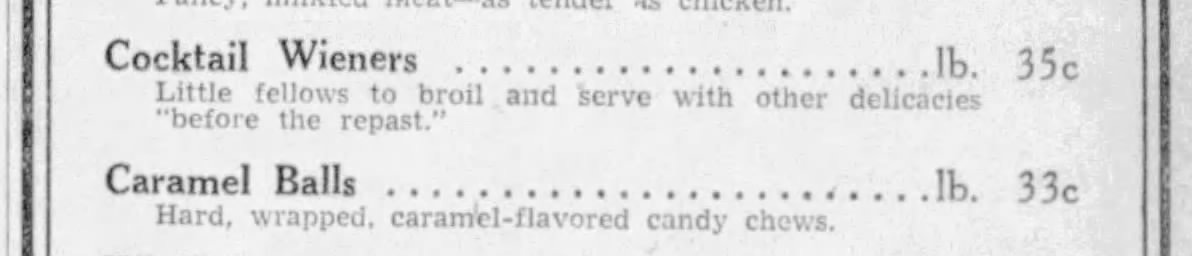

Long before Oscar Mayer smoked his first li’l, there were “cocktail weenies,” the kind designed to be fished out with toothpicks from an ocean of glossy brown sauce. The weenie’s origins haven’t been well dogumented, but the first instance of “cocktail wiener” I could find in print was from 1934—a cursory ad in the Sioux City Journal that promised “something new in a meat.”

The “something new” traveled fast. By 1937, ads for cocktail wieners were showing up in papers across the country—including this one, from the Pasadena Post.

It took decades of study and innovation to birth the smoked ween. Ads for “little smokies” didn’t start appearing until around 1950, with Jones Dairy Farm, Oscar Mayer, and Stark & Wetzel all jockeying for miniature market share.

The name has changed a few times over the years, though the product has remained remarkably consistent. In 1984, Hillshire Farms started running ads for “Lit’l Smokies,” an attempt to differentiate the branding (and stake out a trademark).

I suppose it worked: Hillshire Farms’ “Lit’l Smokies” are still the easiest to find in Midwest grocery stores. But no one I know calls them that. The name never really took off, perhaps because it was impossible to pronounce without sounding like you were bullying Eliza Doolittle.

Instead, everyone just calls them “li’l.”

Introducing: Smoke Sheaths

Li’l smokies are easy to find in KC: Midwesterners never miss an opportunity to eat sweaty meat out of a Crockpot. But the smokies alone were not sufficient for my Tiny Hot Dog dreams. I needed a weenie holster—a smoke sheath—to match.2

On a whim, I reached out to Andrew Janjigian, a longtime baking instructor, recipe developer, and unrepentant breadhead who writes the excellent Substack newsletter Wordloaf. I originally asked Andrew for advice on smoke-sizing a standard hot-dog bun recipe. Instead of ignoring me, like a sane person, he offered to concoct the recipe himself—even after I confessed that I still own (and use) a bread machine.

The resulting recipe for Smoke Sheaths is linked at the bottom of this post. It’s a soft, fluffy, dollhouse bun enriched with milk and butter—a scaled-down version of Andrew’s shokupain de mie. It is also, critically, a New England-style bun, designed to be top-loaded rather than hinge-cut.

Here’s what Andrew told me about the style:

“I think the quality of the bun is more important than the style, but obviously the New England-style bun is superior to others. Leaving the long sides un-crusted makes them either soft and pliant, or (better yet) primed and ready for butter-griddling into crisp walls.”

Another bonus: New-England-style buns stand upright on a party tray instead of crumpling cowardly onto their hinged sides.

Do not lambaste me about the state of my sheet pan, and do not judge Andrew’s recipe by my toddling food styling. (I’m a writer, not a photographer. I’m trying to get better, but I’m not trying very hard.) Despite their pasty Hapsburg appearance, the buns were soft and buttery and absolutely delicious. I tore two of them apart with my bare hands and ate them steaming, dogless, like a lush.

But I also filled them. When Haterade turned two earlier this month, I threw a Tiny Hot Dog party in my living room. I bought condiments to cover as many hot dog styles as I could and tried one of each, plucking dog after dog from the tray with relish (and occasionally, relish).

It didn’t feel exactly the same as eating 40 different hot dogs. The l'il smokie brings its own eldritch flavor to the party.3 But it was close enough to be fun.

I’m sure some people would argue that this experiment isn’t all that different from Nathan’s hot dog eating contest—possibly, they’d argue it’s worse. The American view of gluttony seems more preoccupied with pleasure than consumption. Our national identity was partly forged by Puritans, and I’m not sure we’ve out-paddled our moralistic tendencies.

I’m not sure I have, either. Here I am, ranting about the joylessness of competitive eating, a hedonist clutching her pearls.

But hedonism has never felt like gluttony to me precisely because it’s never felt empty. There’s a difference between consuming and tasting, between a “body count” and falling in love. The difference isn’t volume—it’s attention.

A few years ago, I came into the kitchen and saw my husband contemplating a spoonful of whole grain mustard with rapturous attention. “People fought wars to taste these things,” he said to me, eyes red and wide. “And I get to eat them stoned, out of the fridge.”

Food is about so much more than pleasure, of course. But it is also about pleasure, and I’m tired of being told—implicitly, sometimes explicitly—that pleasure and humor and joy are less serious, less useful, less thoughtful responses to the world.

Getting stoned and tasting mustard is a prayer right up until the point where you call it one. The way to take joy seriously is to take it where it comes.

Reminder: Haterade stickers are in and you can cop one for free! Sticker photo / details on how to claim one here.

If you liked this post, please share, subscribe, or send to a friend! Most new subscriptions come from people sharing a post that they enjoyed. And if you’d like to help me throw larger, more lavish hot dog parties in the future, you can toss a few bucks in the tip jar here: Venmo | PayPal

Underreported is that his father’s name is Merlin Chestnut. MERLIN. CHESTNUT.

While we were working on this recipe, I sent Andrew a few names I was tossing around. He chose “smoke sheaths” because it was the dirtiest-sounding one. This is just to say: he is one of us.

Specifically, Liquid Smoke.

This entire post is pure poetry. Slightly pornographic culinary poetry. Brilliant.

The Cincinnati chili coney is perfect for this, but for two things:

1. the hot dog used is purposefully flavorless. I’d prefer something between it and the li’l smokey and its liquid smoke taste

2. The New England style bun is superior. The local bun is the traditional hot dog bun, but smaller.

That said, it is a good vessel for showcasing the chili and cheese (as well as the mustard and onion, which is the superior way of preparing it.)