Home Economics: Every Month Is the Cruelest Month

On restaurant boosterism and "consumer-oriented" journalism.

If you believe T. S. Eliot, April is the cruelest month. If you believe restaurant enterprise reporting, every month is crueler than the last.

“September is the cruelest month for restaurants,” says Bloomberg. “For Restaurants, January Can Be The Cruelest Month,” counters Forbes. “Savvy restaurant-goers dread August,” writes Steve Cuozzo in the NY Post. “It’s the cruelest month.”

Restaurants tend to operate with thinner profit margins than other types of businesses, making them more vulnerable to normal seasonal fluctuations in demand. It’s not surprising to me that the Lean Times make headlines. What is surprising to me is that no one can seem to agree when the Lean Times are.

“Restaurant Week” and similar tourism-board inventions are ostensibly supposed to give restaurants a boost when they need it most. But there’s little consensus there, either. Kansas City plops its restaurant week in January, when the holiday gluttony has faded and everyone is either punishing themselves with some restrictive diet du jour or swaddled in their homes like a glazed ham. But other cities take a different approach. Boston schedules Restaurant Week in March, San Francisco in April, Phoenix in May. Are any of us doing this right?

Whether Restaurant Week is a good deal for restaurants at all is a separate question. In Kansas City this year, participating restaurants had to pay a $200 registration fee, set their prices at one of three pre-determined tiers, and pledge to donate 10 percent of their sales to a “charity partner and two founding beneficiaries” (the city’s tourism board and the Greater KC Restaurant Association).1

But I’m going to be uncharacteristically charitable and take Restaurant Week promoters at their word when they say their goal is to help restaurants through sales slumps.

So…are they?

What’s the “cruelest month” for restaurants?

To answer this question, I used data on monthly sales at “Restaurants and other eating places” from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Monthly Retail Trade report from 1992 through 2019. I tossed out data from 2020 and 2021 so I could try to answer this question for a more typical year. It’s hard to say right now whether our years will ever be typical again—I, for one, plan to become increasingly unhinged—but I think it’s safe to assume they won’t look exactly like 2020.

Methodology

This is the part of economics papers that most readers skip over. I have tried to make it entertaining, but you have been warned.

It would be tempting to just calculate some averages for that monthly restaurant sales data and poop them into a chart. But I didn’t do that, because I respect (and fear) my readers.

The trouble with using monthly sales data to answer a question like “what’s the worst month for restaurant sales?” is that February is almost always, by construction, going to look like a tire fire.

Consider the Red Lobster:

If my RL franchise sells $5,000 of cheddar biscuits every day in January and $5,500 of cheddar biscuits every day in February, the monthly data is going to show that my sales got worse in February, not better.

January: $5,000 x 31 days of sales = $155,000

February: $5,500 x 28 days of sales = $154,000

True enough, calculating average sales for each month over the 1992–2019 period suggested February was the worst sales month for restaurants. This is inherently suspicious! February sucks on a lot of levels, but at least it’s got Valentine’s Day. People love going to restaurants and spending $100 on a prix fixe menu that ends in a microwaved chocolate lava cake.

For a better comparison, I divided monthly sales by the number of days in each month (yes, I accounted for leap years) and then averaged those values over the full sample as well as a 2015–19 subsample.

If this seems unnecessarily complicated or boring, just know that the goal of all of this was to compare monthly sales while accounting for differences in the number of days in each month.

In hindsight, calling this section “methodology” was pretty generous. There’s nothing all that sophisticated or complex about what I did here. I didn’t even use an “economic instrument,” which is what economists call the large saxophone that performs linear algebra.

To the charts!

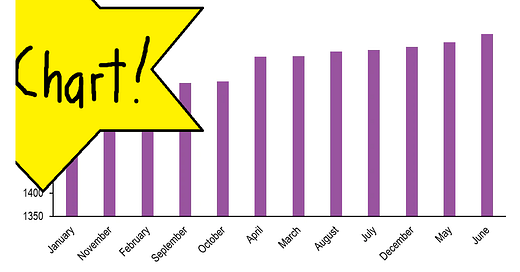

Let’s start by looking at results for the full sample—here’s a chart with the months sorted from cruelest to least cruel.

Chart 1. Average Daily Sales, 1992–2019

Quick note: the data aren’t inflation-adjusted, which means the averages are going to look pretty low over a 30-year period. This is totally fine and cool since I’m looking within months—do not report me to the data police—but it does mean you should focus on the differences between months and not worry too much about the level of sales.

Some interesting stuff nonetheless! I expected January to be at the bottom, but I was surprised at exactly how much January blows for restaurants relative to the rest of the year. It’s not even close.

That said, it’s possible the “cruelest month” has changed more recently, so I performed the same calculations on a smaller 2015–19 subsample.

Here’s the chart for the 2015–19 period:

Chart 2. Average Daily Sales, 2015–19

This chart gave me a little more confidence in my answer. There’s some reshuffling of the mid-tier months—November and February have swapped places for cruelty’s second-in-command—but the pattern is pretty consistent overall. January still sucks the most by a significant margin; June is still a bacchanal.

Why is this “home economics”?

Admittedly, restaurant sales aren’t the most obvious choice for a “home ec” themed column. With the exception of “Sad Martini,” the nightmare restaurant I have long threatened to open in my kitchen, restaurants are about as far from home as you can get.

Here’s my defense: In my intro to this column-within-a-newsletter last week, I wrote about how most basic definitions of economics focus on how people make choices in the face of scarcity. When (and where) to go out to eat on a limited budget is a choice that households make all the time.

Going into the pandemic, Americans were making that choice more than ever. In 2010, we spent a greater portion of our income on “food away from home” than “food at home” for the first time. The pandemic may have temporarily tanked our restaurant spending, but it didn’t kill our appetite for eating out. Restaurant sales appear to have more than recovered from their pre-pandemic levels. The USDA Economic Research Service’s Food Expenditure Series shows that sales of “food away from home” in December 2021 were up 4 percent (adjusted for inflation) relative to December 2019.

And people care deeply about where they buy their “food away from home.” If they can make an informed choice to support their favorite restaurant when that restaurant needs it most, a lot of them will. Yes, customers can be entitled assholes. They’re people, after all, and people are an abnormal distribution of freaks and saints and creeps and psychos. But I also think diners care about the health of the restaurant industry more than critics give them credit for.

When the pandemic started, restaurant critics engaged in a bunch of pearl-clutching about whether it was appropriate for them to act as “cheerleaders” or “advocates for an industry.”

But those debates ignored the fact that customers were picking up the pom poms on their own. During the first few months of the pandemic, there was a huge outflow of support for restaurants from patrons who really loved and missed them—who were willing to buy gift cards, buy merch, even drop off envelopes of cash to help their favorite bartender make ends meet.

I’m trying to write about two things at once here: I want this post to be about “home economics” for the same reason I want writing about labor issues, supply disruptions, and restaurant economics to be considered “consumer-oriented.” You can write about those things without being an industry simp because those aren’t topics that are only interesting to the industry. Consumers deserve to know whether they’re spending their dining dollars wisely—and I think they increasingly do want to know. The popularity of restaurant exposes, the rise and fall of Bon Appétit and its marquee apron models all suggest a broader demand (and audience) for those stories.

If your vision of consumer-oriented journalism is to only write about the things you can see from the dining room, your beat is too narrow. Your idea of what diners care about is, too.

It’s all home ec, baby.

Conclusion and Caveats

This is the part of the economics paper where the writer tells you why everything you just read is wrong.

I don’t think I am wrong, to be clear! I redid this same analysis using a totally different data source—the USDA-ERS Food Expenditure Series—and got similar results overall. January blows no matter which data cake you want to slice.2

But it is worth qualifying that I can only really say that January is, on average, the cruelest month for restaurants nationwide. Different parts of the country might have unique factors that cause them to deviate from that trend. For example, national data suggest restaurants do pretty well in August; in Washington D.C., though, restaurants might see a sales slump, since Congress is out of session and much of the associated $20 Old Fashioned traffic is going to dry up.

Also: I am not an economist. If I am anything, I am an economistake. It is quite likely that there is a fancier, more compelling way to answer this question than the route I chose.

Ideas? Objections? Drop them in the comments. If this whole essay turns out to be a waste of time—well, at least I got to do math.

If you’d like to support the Haterade Center for Not Uncombatting Economic Illiteracy, share, subscribe, or hit that little heart button. Sharing these posts is the best way to help people find the newsletter!

You can also send a tip to lower the opportunity cost of this endeavor: Venmo | PayPal

Members of the Greater KC Restaurant Association received a waived registration fee, but membership in the association costs between $300 and $3,000 depending on the restaurant’s sales.

Specifically, I used monthly sales of “food away from home,” which are available starting in 1997. I swapped in the Retail Trade series at the recommendation of my friend Andy—thanks, Andy, this isn’t your fault!—and I think it’s better by virtue of being a little more narrow. “Food away from home” is a broader data series that includes not only full-service restaurants but also things like catering services and school lunches that are less relevant for the question I wanted to answer (and that might have a different sales pattern, too).

Thank you for the clean nice-looking graphs! The "Consider the Red Lobster" line really cracked me up. It's humor like that that keeps me coming back to your writing. Excellent work!

I like reading about humor, food, and economics, so I'm here for this.

There are so many things going on in the restaurant industry I'm curious about: Ongoing togo liquor sales, being able to buy a gallon of milk from a restaurant with your carryout order during early pandemic, ongoing impact of money-losing delivery apps, why my last three delivery orders were missing items (including rice from a Chinese restaurant which I can't imagine happening in a thousand orders!), how a soup and salad togo order took 75 minutes from an empty restaurant, etc. But I don't want to make anyone's day worse or weirder so I never ask any questions. Meanwhile you're out here graphing up a storm trying to get to the bottom of things. Kudos!